Introduction

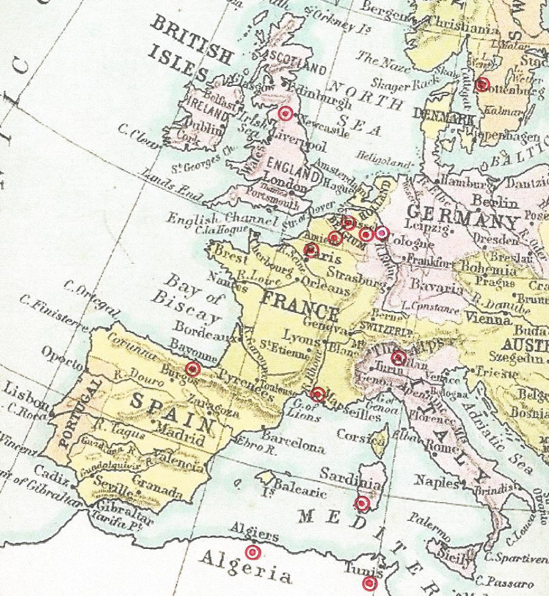

The list of countries concerned so far is Algeria, Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Mexico, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia and the United States. This page brings together an quite large first overview of the VM company’s establishments.

It forms a brief starting point of miscellaneous scraps of information for what will be a much broader and deeper project the association Vieille Montagne Heritage will develop in the coming months.

The content is likely to change frequently as new information comes in. More in-depth information will be added to each individual site further studied, discovered or rediscovered in the country concerned.

Please feel free to contribute anything in whatever language, so far we can deal with English, French, German and Italian.

Vieille Montagne - one of the first ever multinational company

The seeds of the Vieille Montagne Company of Belgium were sown on 19th January 1810, when Emperor Napoleon granted the concession of the Altenberg mine to JJ Dony leading to the construction in Liege of a furnace to extract zinc from calamine.

About the turn of the 20th century the Vieille Montagne was at the peak of its international expansion. By 1905 the Vieille Montagne had seven mining and metallurgical facilities in Belgium, eleven in France, eight in North Africa, three in Germany, two in Sweden, four in the north of England, four in Italy and two in Spain, as well as agencies all around the world !

After the 1st World War, Europe faced competition from new zinc-producing countries, such as USA, Canada and Mexico, as well as contending with the severe post-war depression. This led the Vieille Montagne company to develop its concessions in Sardinia and North Africa.

By the time of the company’s centenary in 1937 the Vieille Montagne had mines and plant in several countries in Europe and North Africa, as well as associated companies there and agencies in Mexico and United States

The involvement of the Vieille Montagne in Algeria began with a mine manager from the Vieille Montagne, Monsieur Mousty, who carried out the first exploratory work. This produced promising results in 1887 and a concession was granted to the company on the 11th December 1890, for zinc, lead and other connected metals in an area initially of 2,559ha. Incidentally, M. Mousty was also involved in the VM mining trials in Wales ten years later.1

The investment met with success. Thirty years later, in 1920, the output for the Vieille Montagne mine at Ouarsenis, near the village of Bou Caid between Orleansville and Tiaret, was 3,194 metric tons of zinc ore.2

With regard to the personnel and administration of the mines, in 1902 the agents for the Vieille Montagne were Poirson & Esperiquette, with their ‘Depot de Zincs de la Vieille Montagne’, for ‘Fers, Toles, Aciers & Metaux,’ at 12, Rue de Constantine. By 1904 this had changed to ‘Poirson & Fevre fils aine’.

Of the Vieille Montagne staff, in 1926, on the 90th anniversary of the foundation of the company, out of a list of 455 names of personnel with long service records, the staff at L’Ouarsenis were Martini Conzales, assistant chief with 22 years, Alric Gabriel, head accountant with 19 years, Albin Lapierre, head of the mining department, 18 years, Emile Jamme, mining engineer, 17 years, and Maurice Deoremps, storeman, 9 years. And of 59 names of those who had retired, Paul Taylor, former engineer director of the agency, had 31 years service, and Rene Tambuyser, former agency accountant, had 16 years.3

At the end of the 1920’s Algeria was hit by the world-wide economic slump. In 1929 there were twenty-five productive lead-zinc mines in Algeria with a combined output that was valued at about Fr.32,000,000.4

Lead production in North Africa for 1930 was; Algeria, 12,800 metric tons, Tunisia, 24,800 metric tons, and Morocco 7,100 metric tons, but by 1933 only three mines were left in production, of which by far the largest and most constant was at Ouarsenis.5

Nevertheless the Vieille Montagne celebrated its centenary in 1937, and its souvenir publication made note of the zinc and lead mines at Ouarsenis and the agency at the port of Bone.

During the Second World War when all mineral reserves were being evaluated, the American A. Williams-Postel, who was looking mainly at reserves of lead, wrote:

“There are several deposits in North Africa. The best lead-zinc mineralized areas in Algeria and Tunisia occur between the Tell Atlas and the Sahara Atlas, toward the eastern end of the massif.

Algeria has the largest output from Djebel Mesloula; the ore is galena. This locality has had an output of 190,000 tons in 25 years. The 1928 production amounted to 9,000 tons.

Other locations that have produced 200,000 or more tons of ore in their mining history are L’Ouarsenis and Kef Semmah (Guegour). These latter localities, however, have produced more zinc than lead. Regions that have produced around 100,000 tons of ore in the course of operations are Sakamody, Ain Arko, and Djebel Felton.”

At that time, 1943, the price of zinc in the U.S.A. was fixed at $0.825 per pound for ‘Prime Western’, which in London was fetching £26.10s. per ton.6 (‘Prime Western’ was zinc with a purity of over 98% zinc and a maximum of 1.6% lead.)

The British government was also looking at war-time mineral reserves, it concurred with Williams-Postel’s view and pointed out that, “Throughout the country [Algeria] as a whole, and unlike Tunisia, zinc is more common than lead.” It also noted that the mine at Ouarsenis was owned by the Societe de la Vieille Montagne.7

1. A Survey of Algeria 1956, Service de Propaganda, d’edition et d’information, Paris; p.lv

2. Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce, Department of Commerce, 25th Year, Commercial Reports, Part 1, 1922, p.65

3. Vieille Montagne 90th Anniversary book

4. Foreign Minerals Quarterly 1938: Lead and Zinc Mines

5. Foreign Minerals Quarterly 1938: Lead and Zinc Mines

6. The Mineral Resources of Africa, Issue 2: A. Williams Postel: University of Pennsylvania Press; The University Museum: 1943: p.39-40

7. Geographical Handbook Series, Naval Intelligence Division; Algeria Vol.2; HMSO, 1944; p.242

NOTE

More information about the Vieille Montagne in Algeria is available. “La Vieille Montagne en Algerie”, transcribed by Rene Brion & Jean-Louis Moreau can be found online (8/4/2018, modified 19/6/2018). These are extracts from periodicals and other source documents for the period 1867 to 1953, available in French on the ‘Les Entreprises Coloniales Francaises’ website at www.entreprises-coloniales.fr.

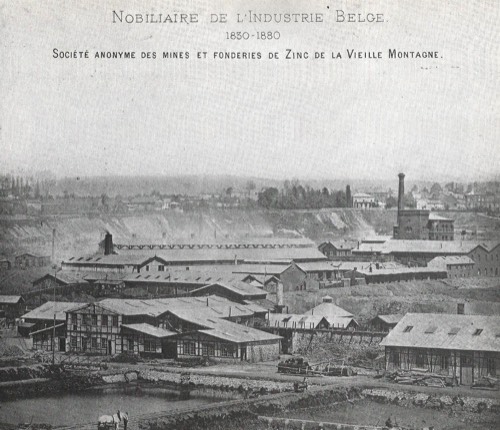

In 1837 La Societe des Mines et Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille Montagne of Angleur was formed in the recently-independent state of Belgium. The company soon acquired rolling mills at Tilff in Belgium and the zinc mine in mini-state of Neutral Moresnet, which became part of Belgium after the First World War. In 1837 there was a foundry at St. Leonard in Liege, and the VM acquired rolling mills at Valentin-Cocq and Flone. In 1837 a factory was under construction at Angleur.

In 1889 the Vieille Montagne built a roasting plant at Baelen-Wezel near Anvers, with the canal nearby for transport. Here, until 1932, blende was roasted to be sent to Flone, Angleur and Moresnet, and an agency was set up at Anvers for the distribution of its zinc products.

Maison de la Metallurgie et de l’Industrie de Liege

The museum recently held an exhibition about employees of the Vieille Montagne, who were recorded on camera in 1868 wearing their work clothes and with their tools and equipment.

Gohltalmuseum, Kelmis

Kelmis was once the hub of Neutral Moresnet, the tiny condominium where the Vieille Montagne first came into being in 1837.

In the centenary year of 1937 the Vieille Montagne in Belgium encompassed its administration and general direction at the Station de Chenee, Angleur, the zinc foundries there, at Valentin-Cocq and Flone, the zinc rolling mills and zinc laboratories at Tilff, and washing plants at Moresnet, Penchot and Cointe. The old plants around Liege and Rhenans were replaced by three factories on the River Meuse. The major centre of production was at Baelen-Wezel, Campine, where there was a factory for the manufacture of sulphuric acid, a lead foundry, a lead rolling mill, and a plant to process cadmium and various other products.

The VM arrived in the hills of Cumberland (now Cumbria) in the north of England in 1896 to take up the leases of a failed company. After a few years of vigorous exploratory trials that included mines in Wales, the company concentrated on the area around Nenthead, a village on the watershed between Cumberland and Northumberland. After surviving two world wars, the economic slump of the late 1920’s, and the natural vicissitudes of the market, the VM left England in 1949.

The mines of zinc and lead were all in a small radius that encompassed Nenthead, Coalcleugh, Rotherhope and Nentsbury. The short-lived but intensive Welsh trials had been at Hafna and Holway in Flint, and at Llangynog in Montgomery.

England

Nenthead Mines Conservation Society, Nenthead Cumbria (nentheadmines.com)

Nenthead was the centre of Vieille Montagne operations in Britain, from where 60% of the UK’s output of zinc ore was produced.

North of England Lead Mining Museum, Killhope, Cowshill, Co. Durham (killhope.org.uk)

Although not part of the VM empire. Killhope is not far from Nenthead and it provides an excellent display of mine conditions through the ages, as well as exhibits of other minerals.

Scotland

The Museum of Lead Mining, Wanlockhead (www.leadminingmuseum.co.uk)

Many Italian miners lived and worked here in similar conditions to Nenthead. Research needs to be done to find out whether any actually came here from Nenthead.

Operations in France commenced more or less concurrently with the establishment of the Vieille Montagne Company when, in 1837, the VM acquired a rolling mill at Bray. The production of zinc in 1837 was 1,833 tonnes, one hundred years later, in 1936, production was 120,000 tonnes.

In 1855 a factory was established for white lead at Levallois-Perret near Paris. In 1871 Auveryon-Viviez became centre of the electrolytic production process. At Penchot there was also a rolling mill.

In 1884 the VM set up a rolling mill at Dangu, near Bray, and a mine at La Croix de Pallieres. A few years later, by 1887, there was a depot, as well as company administration for the north of France, at Hautmont near to the Belgian factories.

During the Great War the French factories of the VM were turned over to munitions. After the war the VM set up a foundry at Creil and a washery at Port du Bouc and soon afterwards, in 1922 hydro-electric processes were introduced at Viviez (Auveryon).

The VM had an associated company in France, the Societe des Gisement Minien de Luz-et-Sauveur, for the exploitation of blendes.

By 1937, the Vieille Montagne operations in France consisted of its French headquarters at 15, Rue Richer, Paris, a mineral reception agency at Bordeux, washeries at Viviez-Averyon and Port-du-Bouc (Bouches du Rhone near Marseilles), a zinc foundry at Creil (Oise), a zinc white factory at Levallois-Perret, zinc rolling mills (where there were usually zinc laboratories as well), at Auby, Bray (Seine et Oise), Dangu (Eure), Hautmont (North), Penchot (Aveyron), and lead and zinc mines at Mines du Gard.

Introduction

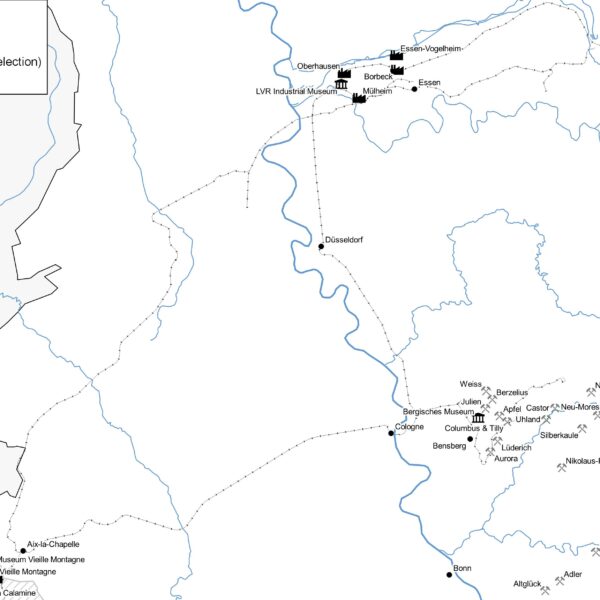

The Vieille Montagne was Europe’s largest producer of zinc, and Germany was home to Europe’s first and largest lead and zinc refiner/smelter.

From early in its history, the VM had business associations in Silesia and Preuss Rhenane with mines at Bensberg in the district of Koln. There were foundries at Mulheim and Borbeck, and rolling mills and washeries at Oberhausen. The mine at Luderich, Bensberg closed in 1978.

In Germany the VM was associated with AG des Altenbergs fur Bergbau und Zinkhuettenbetrieb in Bensberg, where there were zinc & lead mines, in Essen-Borbeck where there was a washery, an acid manufactory and a zinc foundry, and at Oberhausen where there were zinc rolling mills.

LVR Industrial Museum, Oberhausen

Oberhausen is one of several Industrial Museums of the Rhineland, appropriately housed in an old zinc factory.

Bergisches Museum, fur Handwerk, Bergbau. This miniature ‘Beamish Museum’ is in an area where at least two of the German mine managers came from.

The Vieille Montagne in Germany

The first attempts by the Vieille Montagne to become active in Germany took place in the middle of the 19th century, not long after der VM was founded. By this time Germany was not a unified state but a community of loosely affiliated kingdoms, duchies and principalities. However, these states formed an economic union, the so-called Zollverein.

One of the purposes of the Zollverein was to protect domestic markets from superior foreign goods. By the middle of the century the German economy was still on the eve of industrialisation. The industries especially in Belgium and Great Britain were more developed than the German. To hold back competition from those industrial countries the governments of the Zollverein states imposed high tariffs on industrial goods like zinc products.

To evade to tariffs the VM decided to set up a production site on German territory as early as 1838. They first tried to take over a smelter in Aix-la-Chapelle just on the other side across the border. As those plans could not be realized, the VM made another approach in 1852. That year the VM founded the subsidiary Société des Mines et Usines à Zinc de la Prusse-Rhenane together with shareholders of the bankrupt company Antonius which owned mines near Bensberg and a smelter in Mülheim an der Ruhr. Moreover, the Société Prusse-Rhenane took over the smelter in Essen-Borbeck and further mining sites in different German regions. But as early as 1853 the VM merged with the Prusse-Rhenane company.

The area the VM selected for its new facilities was wisely chosen. Around 1850, companies began to develop iron ore and large hard coal deposits in the so-called Ruhr Area. Favoured by these raw materials as well as railways and shipping lines that were built from 1846, many huge heavy industry companies emerged. Industry, infrastructure and construction of residential buildings for the new industry’s workforce promised to generate a great demand for zinc products.

In the following decades the VM kept expanding it’s mining and manufacturing capacities in Germany. The German mines and production sites remained under direct administration of the VM. During World War I the German VM facilities were separated from the corporation’s other plants. The German sites provided zinc and sulphuric acid, a basic material for explosives, for the German war efforts.

Overview of the VM Industrial Sites in the Ruhr District, 1850-1981

Map by: Geschichtsbüro Sobanski

The relationship between the German sites and the VM changed permanently in 1934. The national-socialist regime treated foreign companies, especially in the basic industries, with suspicion. To be safe from possible confiscation and to be able to benefit from state subsidies for industries essential to war efforts, the VM formed a German subsidiary named Aktiengesellschaft des Altenbergs. This company remained independent until the end of the 20th century.

Sources and Literature

– Becker, Susan (2002): Multinationalität hat verschiedene Gesichter. Formen internationaler Unternehmenstätigkeit der Société Anonyme des Mines et Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille Montagne und der Metallgesellschaft vor 1914, Stuttgart.

– Rapports du Conseil d’Administration sur les activités de la Vieille Montagne cours de la guerre 1914-1918, Avril 1919, Documentation Centre for Mining History at the German Mining Museum Bochum, BBA 80/122

– Rapports du Conseil d’Administration et des Commissaires Assemblée Générale du 4 Mai 1935, Documentation Centre for Mining History at the German Mining Museum Bochum BBA 80/138.

(1) Mülheim an der Ruhr

Usine de Mülheim s/Ruhr, Lithography by Adrien Canelle, around 1855

LVR Industrial Museum

The smelter and zinc-oxide-factory in the community of Eppinghofen was established in 1845 by the French Société Antonius. After the company went insolvent, it was taken over by the Société des Mines et Usines à Zinc de la Prusse-Rhenane which was founded by and 50% owned by the Vieille Montagne.

The smelter combined roasting and reduction furnaces for the production of raw zinc and oxidizing furnaces for the production of zinc white as basic material for pigments. Especially the roasting furnaces turned out to be a major problem. Neighbouring farmers and landholders constantly complained about the destructive effects the exhaust gases of the roasting furnaces had on their farmlands. The sulphurous acid that occurred when the sulphide zinc ores were roasted caused major damage to plants and livestock.

The protests and claims for compensation finally prompted the VM to relocate the roasting plants to Oberhausen. They built further reduction furnaces instead. From then on, the zinc ores had to be roasted in Oberhausen. The roasted material was transported to Mülheim for the second step, the reduction. Afterwards the raw zinc was brought back to Oberhausen for further processing.

In 1871 or 1872 a central building of the smelter burned down. The VM finally decided to give up the site and shut down the smelter by the end of 1873. The remaining structures were sold to the iron smelter and foundry Friedrich Wilhelms-Hütte. The contract prohibited to use the buildings and facilities for zinc smelting. The last remaining structure, the administration building, was demolished in 1971.

Sources and Literature

– Sales contract between the Société de la Vieille Montagne and the Bergwerksverein Friedrich Wilhelms-Hütte, 18.1.1872, Foundation for the Thyssen Industrial History, FWH/1005.

– Der Bergwerksbetrieb in dem Preussischen Staate, in: Zeitschrift für das Berg-, Hütten- und Salinenwesen im Deutschen Reich (1855-1873).

– Mittheilungen. Mülheim a.d. Ruhr 10. Nov., in: Der Berggeist (1872), p. 591.

– Becker, Susan (2002): Multinationalität hat verschiedene Gesichter. Formen internationaler Unternehmenstätigkeit der Société Anonyme des Mines et Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille Montagne und der Metallgesellschaft vor 1914, Stuttgart.

– Bruch, Claudia (1997): Zink Altenberg, in: Rheinisches Industriemuseum Oberhausen (Ed.): Schwerindustrie, p. 22-41.

– Seeling, Hans (1983): Wallonische Industrie-Pioniere in Deutschland. Historische Reflektionen, Liége.

(2) Essen-Borbeck

Usine de Borbeck, Lithography by Adrien Canelle, about 1855

LVR Industrial Museum

The second VM smelter on the Ruhr was founded in 1847 by Lecomte & Co. in Borbeck, in what is now the city of Essen and later operated by the Société de Nassau. It was located right next to the train station Bergeborbeck of the Cologne-Minden Railway Company, the first railway line in the region. After its insolvency the smelter was taken over by the Société de la Prusse-Rhenane and thus became property of the VM.

The smelter combined calcination, roasting and reduction processes. After the closure of the other smelter in Mülheim the plant in Borbeck partly used roasted zinc ore from the roastery in Oberhausen. The finished raw zinc from Borbeck was then brought to Oberhausen for refining and rolling. Both factories were directly connected by the railway line.

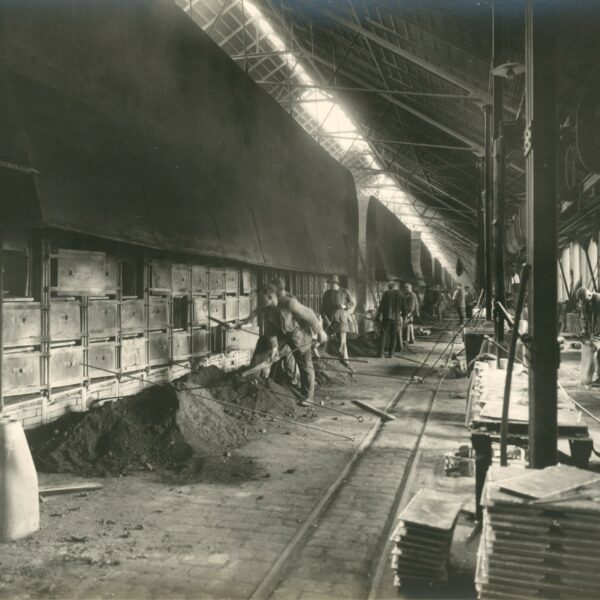

Reduction Furnaces at the Borbeck Smelter, around 1900

Centre d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques de l’Université de Liège

A major fire in 1919 destroyed several buildings. Therefore, the VM decided to rebuild and expand the smelter. By 1929 the company established larger roasting and reduction capacities and added a sulphuric acid plant to the site. Subsequently the VM ceased the roasting processes in Oberhausen and concentrated raw zinc production completely at the Borbeck site.

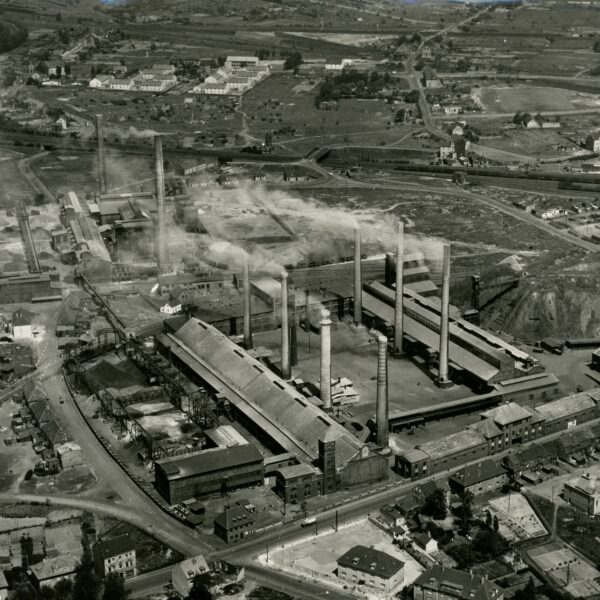

Smelter Borbeck, around 1950

Centre d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques de l’Université de Liège

Shortly before the beginning of World War II the smelter was further expanded. The sulphuric acid production in particular was vital for armament production during the war.

An unknown number of forced labourers from both western and eastern Europe was compelled to work on the Altenberg site. Two forced labour camps are documented.

As an important plant with other industrial facilities, mines and a train station in close proximity, the smelter became a target for Allied air raids. In 1944 at the latest the smelter broke down after heavy damage.

After the end of the war the smelter soon resumed operation, but the zinc industry in general began to change. Electrolysis was about to replace the older pyrometallurgical processes which were still used in smelters like Borbeck. But the great amounts of energy that an electrolytical plant consumed made it urgent to concentrate the zinc production in a small number of large facilities. The smelter in Borbeck failed to meet the competition and the Altenberg company had to close the factory.

The zinc reduction plant was closed in 1968, the sulphuric acid plant in 1976. Smaller workshops producing galvanized steel grids remained operative until 1981 when the Borbeck and Oberhausen works were relocated to Essen-Vogelheim. The buildings were completely demolished and the city of Essen built residential buildings, but without removing the contaminated soil. The ground was cleaned subsequently so that people can live on the former industrial site today.

Sources and Literature

– Becker, Susan (2002): Multinationalität hat verschiedene Gesichter. Formen internationaler Unternehmenstätigkeit der Société Anonyme des Mines et Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille Montagne und der Metallgesellschaft vor 1914, Stuttgart.

– Engelskirchen, Lutz (2007): Zink: das achte Metall, Essen.

– Koerner, Andreas (1999): Zwischen Schloss und Schloten. Die Geschichte Borbecks, Bottrop.

– Wisotzky, Klaus (2001): Zwangsarbeit in Essen, Essen.

– Der Bergwerksbetrieb in dem Preussischen Staate, in: Zeitschrift für das Berg-, Hütten- und Salinenwesen im Deutschen Reich (1855-1873).

– Uebersicht der Zinkhüttenprocesse, in: Berg- und Hüttenmännische Zeitung (1895), p. 101.

– N.N. (1925) Die Borbecker Zinkhütte der Aktiengesellschaft des Altenbergs (Vieille-Montagne) in Essen-Bergeborbeck, in: Deutschlands Städtebau – Essen, p. 261.

– Accounts of revenues and expenditure, 1928-1929, Documentation Centre for Mining History at the German Mining Museum Bochum, BBA 80/301.

– Stolberger Zink Aktiengesellschaft für Bergbau und Hüttenbetrieb, Altenberg-Betrieb Zinkhütte to Rüstungskommando Essen, 1944, Documentation Centre for Mining History at the German Mining Museum Bochum, BBA 80/307.

– Supervisory board record of the AG des Altenbergs, 1967, Documentation Centre for Mining History at the German Mining Museum Bochum, BBA 80/3940.

(3) Oberhausen

Usine d’Oberhausen, Lithography by Adrien Canelle, around 1855

LVR Industrial Museum

When the Vieille Montagne or rather its subsidiary the Société Prusse-Rhenane took over the smelters in Borbeck an Mülheim it still lacked a facility to process raw zinc into finished goods. Therefore, the company bought a piece of land in today’s city of Oberhausen. The town however did not yet exist. In 1847 a train station was built on the new railway line between Minden and Cologne. Around this station and the neighbouring coal mines an industrial agglomeration evolved that later led to the foundation of the city Oberhausen.

The VM established a small rolling mill in 1854 that was supplemented by a roasting plant in 1857 when the respective facilities in Mülheim were shut down. In the second half of the 19th century, the industrial site was continuously expanded. By the end of the century there was a large rolling mill and two roasteries that were connected to a neighbouring sulphuric acid plant. The rolling mill included workshops for the manufacturing of roofing material.

Roasting Furnaces, around 1900

Centre d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques de l’Université de Liège

The emissions from the roasting plant and other industrial sites polluted the ground water in Oberhausen. Thus, the VM saw itself forced to participate in the foundation of a water company to supply the city of Oberhausen, but mainly the city’s industrial companies. This is only one example for public services that the newly founded city of Oberhausen could not provide by itself. The VM also established its own fire brigade which also worked for the general public.

Workers’ Colony Gustavstraße, around 1900

Centre d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques de l’Université de Liège

Around the turn to the 20th century the VM modified its factory extensively. The rolling mill and the older roasting plant were connected. A large boiler house and an electrical power station were built. The manager received a mansion with a garden and even a palm house. During the decades before the VM had already constructed two workers’ colonies next to the site.

Rollers power by electrical motors, around 1920

Centre d’Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques de l’Université de Liège

The roasting plants remained in operation until the new facility in Borbeck took over in 1929. Most of the buildings were destroyed in World War II. In this war zinc again was a vital material. Therefore, the Nazi government subsidized the zinc industry and the VM turned the German works into the independent company AG des Altenbergs. Zinc was important not just for armaments manufacturing itself, it also was used to substitute other war materials such as aluminium or copper. The Altenberg rolling mill for instance produced Reichspfennig coins made of zinc.

At least 30 POWs and civilian labourers, mainly from the Soviet Union, male and female were forced to work in the rolling mill and the other workshops of the AG des Altenbergs in Oberhausen. The number of slave workers killed during the war is unknown.

In the 1950s the AG des Altenbergs established two new workshop buildings that replaced one of the roasting facilities. By this time the subsidiary company Kräussl & Co. started producing zinc sheets with a special chemical coating that were sold to printing companies. Another new product of Altenberg was zinc alloys for automotive and other industries.

Workshop for roofing materials, around 1970

LVR Industrial Museum

Despite the innovations of the last decades the AG des Altenbergs had to face economic challenges. Zinc was replaced by plastic in different products and more competitors entered the world market. The end of the zinc works in Oberhausen was initiated by urban development projects. After the shutdown of the Concordia coal mine right next to the zinc works the city of Oberhausen wanted to completely rebuild the entire borough and establish shopping and residential areas.

Discotheque “Schlosserei” (Metalworking Shop), 2006

Zentrum Altenberg

The manufacturing facilities of the AG des Altenbergs were relocated to Essen-Vogelheim in 1981. The development

projects failed, however, as the plans proved far too ambitious. The citizen movement Initiativkreis Altenberg occupied the industrial buildings and turned the site into a cultural centre. Today the Altenberg Zinc Works is the headquarter of the LVR Industrial Museum. The former rolling mill is one of the seven museum sites and the seat of the museum’s administration and central workshops. Moreover, Altenberg is still a grass roots cultural centre with a discotheque, a concert and event hall, a cinema, an art gallery, as well as historical, cultural and social institutions.

Sources and Literature

– Becker, Susan (2002): Multinationalität hat verschiedene Gesichter. Formen internationaler Unternehmenstätigkeit der Société Anonyme des Mines et Fonderies de Zinc de la Vieille Montagne und der Metallgesellschaft vor 1914, Stuttgart.

– Bruch, Claudia (1997): Zink Altenberg, in: Rheinisches Industriemuseum Oberhausen (Ed.): Schwerindustrie, p. 22-41.

– Engelskirchen, Lutz (2007): Zink: das achte Metall, Essen.

– Schmenk, Holger (2009): Von der Altlast zur Industriekultur. Der Strukturwandel im Ruhrgebiet am Beispiel der Zinkfabrik Altenberg, Bottrop.

– Sobanski, Daniel (2021): Verderbniss des Grundwassers. Die Entwicklung der öffentlichen Wasserversorgung in Oberhausen im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Schichtwechsel…

– Sobanski, Daniel (2022): Die Entstehung eines authentischen Ortes der Hochindustrialisierung, Zinkfabrik Altenberg https://zinkfabrikaltenberg.blog/2022/10/06/__trashed-3/.

– Mitarbeiterverzeichnis der AG des Altenbergs, 1942-1950, LVR Industrial Museum rz 02/570.

(4) Essen-Vogelheim

The last chapter of the Vieille Montagne’s history in Germany is rather short. In 1981 the workers and machinery from the two sites in Oberhausen and Borbeck were transferred to a new location in Essen-Vogelheim near the communal port on the Rhine-Herne-Canal. In Vogelheim the company, now called Altenberg Metallwerke, kept producing zinc sheets for printing purposes but concentrated on galvanized steels grids and small-scale industrial maintenance services. The factory did not prove profitable and was closed after the merger with Union Minière. But VM Building Solutions still maintains a sales office in Essen.

Sources and Literature

– Schmenk, Holger (2009): Von der Altlast zur Industriekultur. Der Strukturwandel im Ruhrgebiet am Beispiel der Zinkfabrik Altenberg, Bottrop.

– Altenberg Metallwerke: Grating Handbook, LVR Industrial Museum rz 16/67.

(5) Silesia

In the 19th century the Vieille Montagne mainly operated in the western and southern regions of Germany but also tried to get a foothold in Upper Silesia in the east of Germany.

Upper Silesia now belongs to Poland but used to be a part of Prussia until the end of World War I. The area was the second important mining and industrial district in Germany alongside beside the Ruhr. Because of rich coal and ore deposits it was industrialized even before its western counterpart. For instance, the first coke blast furnace in Germany was operated in a state-run ironworks in Silesia. Silesia also became a centre of zinc production with a zinc industry that in fact was a serious competitor to the VM. One motivation for expanding into Germany was the desire to force Silesian manufacturers to negotiate on a cartel.

But the VM went further. Together with German traders and bankers the entrepreneur Count Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck founded the Schlesische Aktiengesellschaft für Bergbau und Zinkhüttenbetrieb (Silesian zinc mining and smelting stock company, short: SCHLESAG) in 1853. Henckel von Donnersmarck was a noble landowner and proprietor of calamine deposits. He also had personal ties to France. Therefore, the VM was an obvious partner for the foundation of SCHLESAG. Leading members of the VM joined the supervisory and the administrative boards of the company, but after only about four years the VM lost interest and seems to have withdrawn from the company.

Sources and Literature

– Dobbelmann, Hanswalter (1993): Das preußische England. Berichte über die industriellen und sozialen Zustände in Oberschlesien zwischen 1780 und 1876, Wiesbaden.

– Rasch, Manfred (2016): Der Unternehmer Guido Henckel von Donnersmarck, Essen.

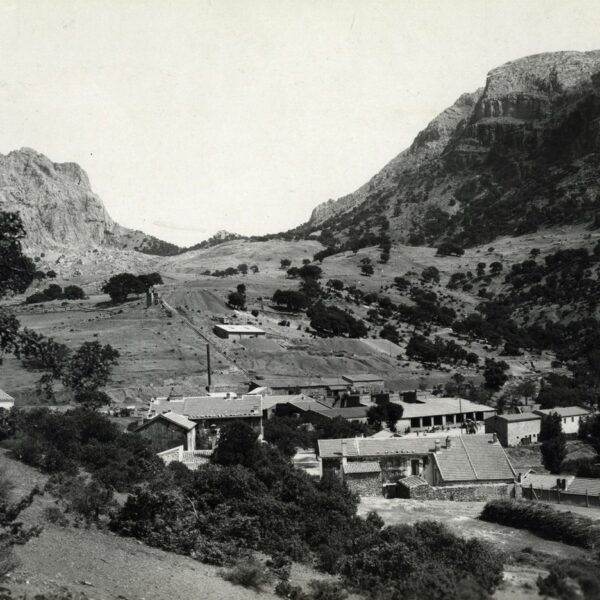

The Vieille Montagne had mines and works in Italy from the mid 19C onwards. A zinc and lead mine is known to have been in existence at Iglesias in Sardinia in 1865 and another at Bergamo in 1889. The VM was still at Bergamo in 1937, where it also had a washery, as well as its unique mechanical loading dock at Porto Flavia in Sardinia.

In Italy the VM was associated with Soc. della Mineire de Lanusei for the exploitation of blendes, galenas and quartz.

Macugnaga

This was a gold mining area high in the Italian Alps, was the home of miners who came to work in Nenthead.

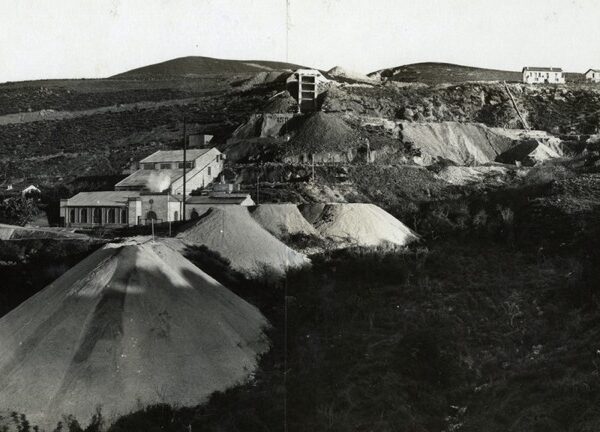

Sardinia

n the 20th century the VM worked several mines on the island, where there is now a strong interest in the history of mining and a European Geopark.

In the late 19th century the VM acquired mines here, but no research has been done so far.

In Mexico the VM was associated with Co. Mexicana el Zinc for mining concessions with the Jesus group in the state of Guerrero.

In the late 19th cenury the VM acquired mines here, but no research has been done so far.

In Spain the VM was associated with Sociedad Miniere de Victoria for the exploitation of blendes, galenas and quartz.

Sweden is home to one of the Vieille Montagne company’s oldest overseas operations, having been there for over 150 years.

In 1937, the centenary year, the company owned zinc and lead mines at Zinkgruvan, near Orebro, Ammeberg and its agency was in Gothembourg. In that year it was reported that the VM sent lead concentrates to Boliden’s Ronskar plant and zinc to its own facilities in France.

The mine at Ammeberg, where the company had been since at least 1857, produced 25% of Vieille Montagne’s ore requirements.

While examining the mineral reserves of North Africa in 1943, the American A. Williams Postel noted that “Tunisia also has a fair lead mining industry.”1 The first exploratory trials carried out were by the Vieille Montagne in 1876, at the same time as those in Algeria. Concessions were granted on 6th May 1876 for zinc and lead at Djebel-ben-Amar, and for Djebba and Djebel-ben-Amar on 27th January 1900, to cover an area of 615 acres.2

Exploitation took a little while to develop but when it did, it did so rapidly. In 1893 there were only two mines in operation, ten years later there were seventeen.3

In 1903 the Vieille Montagne was among thirty-two mining companies operating in Tunisia, employing as it did seven Europeans and thirty-seven locals. That year the value of the company’s production was Fr.55,628 for an output of 1,081 tons, but in the list of mining and other associated companies the VM in Tunisia was only middle ranking.4

In 1937 the Vieille Montagne listed the galena mines at Djebba among its widely distributed mining sites.5

1. The Mineral Resources of Africa, Issue 2: A. Williams Postel: University of Pennsylvania Press; The University Museum: 1943: p.39-40

2. 1900 Annales des Mines Neuvieme Serie, Minister of Public Works. Lead and zinc concessions p.217 & 218

3. The Echo of Mines and Metallurgy, 9/1/1905; Mines in Tunisia; Francis Laur

4. The Echo of Mines and Metallurgy, 9/1/1905; Mines in Tunisia; Francis Laur

5. Vieille Montagne Centenary 1837-1937

About the turn of the 20th century the Vieille Montagne was at the peak of its international expansion. Zinc had only found a market in the previous two years and was therefore a comparatively new industry, at least in the USA where it had formerly been a by-product, the waste in the tailings heaps.

The VM entered the American market in 1899 and shipped large quantities of zinc ore from the Leadville district of Lake County, Colorado to Antwerp. Shipments were also made to Swansea in Wales for spelters there.

In 1899 it was recorded that a “solid train of 30 cars, or 25,000 sacks, has been loaded with zinc ores for the Vieille Montagne at Antwerp. The cars go to Galveston, and the shipment is made through A.J. Davis for Jacobson & Co. of New York City. The shipment is the largest of any kind of ore ever sent out to any foreign port.”

In 1900, about 14,000 tons of zinc ores were shipped to the VM works in Belgium via Galveston (2,273 tons) and New Orleans (9,150 tons), 6,000 tons more than in 1899.

Franklin Mineral Museum, Franklin, New Jersey

Between 1896 and 1900 the Vieille Montagne Zinc Co. held leases for eight lead and zinc mines in Wales. The mines, which were only trials for the VM, were Holway in Flintshire, Talargoch in Denbighshire, Llangynog, Cwm Orog, Craig Ddu, Cwm Glanafon and Craig-y-Mwn near Llangynog in Powys, and Hafna near Llanrwst in Conwy.

Some Italian miners went from Wales to work at Nenthead in Cumberland, as it was then.